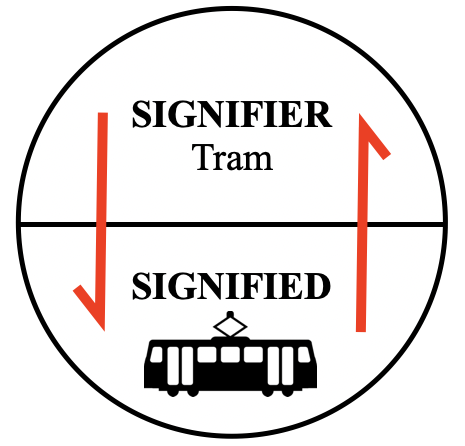

This diagram illustrates the basic model that the Sausseurean semiotic operates upon: a synchronic relationship between signifier and signified. An encounter with a concept, a tram perhaps, illustrates this well. When encountering this concept as written or discussed, it is generally immediately differentiated as such (a tram) by our recognition of a commonly agreed sound pattern, that is, a psychological impression of the sound (tɹam); this is the signifier for the object. This sound pattern, by virtue of conventional use, conjures the correlating object (the signified) in the interpreter’s mind. Saussure explains this in more depth, but fundamentally he identifies an ‘intimate link’ between concept and signifying pattern. The inverse works too: “What is that vehicle driven by electricity, that runs along the streets of a town and carries passengers?” “It’s a tram.”

Saussure identifies this relationship as critical to the conception of a sign, but also as arbitrary. “There is no internal connexion, for example, between the idea “sister” and the French sequence of sounds s-ö-r which acts as its signal,” but it still functions as a sign, due to the commonly understood concept (the signified) which we attach to the signifier.

It follows then, that is not the explicit word itself that carries the ‘sense’ of the thing. Signs take on meaning based on the context within which they signify; we only understand signs in their difference to other signs. For Saussure a value needs at least two constituent elements:

Values always involve:

(1) something dissimilar which can be exchanged for the item whose value is under consideration, and

(2) similar things which can be compared with the item whose value is under consideration.

Ferdinand de Saussure, R. Harris (trans. ed.) Course in General Linguistics, p. 113

To understand a sign, we understand it in its context; we understand its general meaning from all that it is directly dissimilar to, and we understand its specific meaning in all that it is like, yet less dissimilar to.

There is more to this. But this is the fundamentals. Saussure doesn't really capture the natural implications of these ideas for me anyway. Peirce articulates them best and actually accounts for them in his models. Barthes deals with them heavily in his work on semiotics.

Barthes' Intervention

I'm not going into this in any detail. But some notes on a key intervention by Barthes may be helpful.

I forget exactly which text he explains much of this in - I think it might be Mythologies. I don't actually really enjoy his intervention: I think it's unnecessary, needlessly complicating an already-flawed system. I prefer Peirce's system. This being said, Saussure and Barthes are the standard guys here. So I'll add some more notes. This is me attempting to add some clarity to notes I made when I first encountered this about 5 years ago.

Barthes seeks to add depth to things like artistic, literary, and pictorial signs in an attempt to show how we communicate through associated meaning; this also accounts for context of language in a way that Saussure supposedly doesn't:

Signifier + signified = sign

“Rose” + 🌹= Rose

Barthes introduces a slightly different one.

Sign [the new signifier] + signified = new sign [second order]

Rose + passion = ‘the mythical signified’

(Myth = ‘a sum of signs’)

I don't think it needs to be as complicated as it's made out to be: essentially what Barthes is explaining is the difference between a word and a symbol (I've misused some technical terms here for better clarity because in reality all words are symbols).

So for Barthes things have a literal meaning and a symbolic//mythical meaning. The connection between the mythical signifier and signified is in this case not arbitrary but is always motivated; this is to say it is contingent on things like ideology, society, social norms . Social media is a good example: people put up the images of their life that they want people to see (signs) in order to give the impression that they live in a certain way (myth). This is not arbitrary as these images are being used to communicate a specific impression.

Peirce's Triadic Model

Okay so this is one of the more complicated things that I ever had to get my head around

Charles Sanders Peirce’s theory of signs was under development throughout his life, and as such is not distilled or collected under a single definitive text; further to this, many of Peirce’s ideas changed as he developed his theory,leaving parts of his work redundant, and others unexplained. Informing my understanding then is a multitude of secondary and primary literature on Peirce, but the text I relied most heavily on was James Jakób Liszka’s A General Introduction to the Semeiotic of Charles Sanders Peirce (1996). I'll see if I can find a copy to upload.

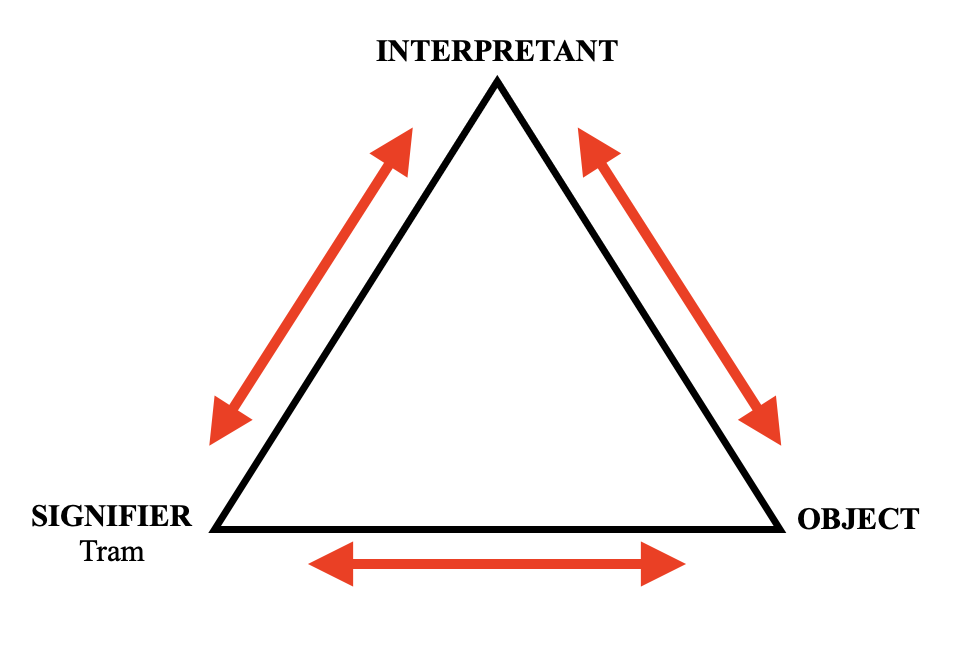

In Peirce’s model, the signifier remains unchanged. It is usually labelled ‘the sign’ but I have left it untranslated for clarity’s sake; Peirce’s language often obfuscates the theory. And the object is, in essence, the same as the Sausseurean signified, although there is some critical added nuance which I will expand upon shortly. Where the model differs most drastically though is in its proper inclusion of the interpretant; that is, “the translation of the sign” If “a sign is not a sign unless it translates itself into another sign in which it is more fully developed”, then the interpretant is this translation in the process of semeiosis which yields the ‘more fully developed’ sign (a thought/ understanding). This inclusion hinges on one rather trite observation: a sign only signifies by virtue of its being recognised as a sign, and being interpreted as such.

It is also incredibly important to note that for Peirce, the object was split into two parts: the dynamic object and the immediate object. For Peirce, “what makes something an object of a sign is the fact that it is represented as such by the sign (the result being the so-called immediate object of the sign) and that it serves to offer resistance, to provide a constraint, or, in general, to act as a determinant for the process of semeiosis which represents it, in which case it is the dynamic object”. The relationship between the dynamic object and the immediate object is best thought as both essential and synchronic; the two are not separable and both must be present for the sign to function: the sign must both convey something and have something to convey. In other words, the division of the object in Peirce’s theory of signs allows us to distinguish the object as represented by the sign (think of this as a subjective view of Odradek) and as determining of the sign (this is as close as Peirce gets to Saussure’s ‘commonly understood idea’).

The only other bit of nuance I'll add here is that for Peirce, the interpretant could be characterised into several different modes. I'll outline three: immediate, dynamic, final.

The dynamic interpretant, on the other hand, consists of the direct or actual effect produced by a sign upon some interpreting agency; it is that which leads to “whatever interpretation any mind actually makes of a sign”. Here, it is best thought of as the critical reading of the sign.

The final interpretant is that which leads to the interpretation “which would finally be decided to be the true interpretation if consideration of the matter were carried so far that an ultimate opinion were reached”. This is where we can find the ‘true meaning’ of a sign.

[“For Peirce, a true belief is not simply one we will hold onto obstinately. Rather, a true belief is one that has and will continue to hold up to sustained inquiry. In the practical terms Peirce prefers, this means that to have a true belief is to have a belief that is dependable in the face of all future challenges.” For further reading, see source: John Capps, “The Pragmatic Theory of Truth”, in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.]

The main draw to Peirce is his thoroughness, I may expand on this later because it's a hill that I really will die on. But Peirce's system is better. It covers all of the gaps that Saussure leaves, has much wider applications and implications, and is just far better suited for utility. That being said: Peirce was after all a Pragmatist.